A joyous walking tour through island history

I was fortunate enough to have access to some of the stories that were passed on to family members as well as those in the community whose relatives were involved.

These were events that changed the fortunes of those living there today, and we do well to remember them, and honour the memory of those who fought for those rights, which by definition, have now become our rights.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHistory is a curious thing, especially when it concerns my own heritage, as I come face to face with the serious gaps in my knowledge – I could blame how it was dished up at school, less than palatable or lacking in relevance.

There are however no excuses for the gaps in my grasp of local geography, a subject that is as fascinating as it is varied. If you’re like me, let me recommend a wonderful book that landed in my letter box last week.

It was a preview copy of Marc Calhoun’s personal experiences of thirty years of hiking through the Outer Hebrides, forensically researched and containing the most compelling photographs as well as maps – particularly useful for people like me who would struggle to pinpoint Mealasta or Rona on a map.

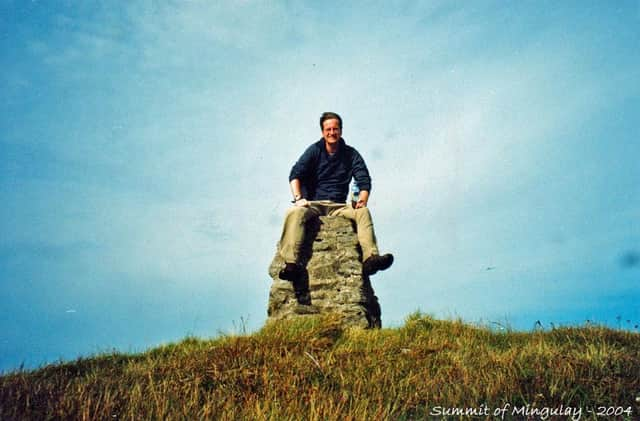

Helpfully laid out in seven parts, corresponding to the different areas or islands, from Mingulay in the south to Rona and Sulasgeir in the north, Marc takes us on a walking tour through history, much of which involves bargaining with the weather. No stranger to these shores despite living in Seattle, his love and fascination for the natural heritage of this remarkable corner of the world calls loudly and clearly from his collection of photographs that accompany the text.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Barra isles to Eriskay with which he starts his ‘journey’ begins with an account of flying from Glasgow to Barra on a Saturday morning in February. It was as if he couldn’t wait to explore his new habitat, walking or climbing and recording the sights and the stories behind them, from tragedies to victories, all the myths and legends that made their way down the years.

Travelling with Marc, because that’s what it feels like when he’s describing some of his journeys, is a combination of fear and excitement – the former because of the uncertainty that you will ever get anywhere, thanks to the elements, but the excitement if you should strike lucky. He’s clearly a patient man, otherwise he would have accepted defeat at the hands of the Hebridean gales.

Part two covers the Uists and inevitably, tales of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the summer of 1746 as the author treks through history as recorded by the poets of the day. There are tales of battles fought and won, and it’s hard to believe now that such bloodthirsty events ever occurred in places of such piety and beauty.

There are chapters on St Kilda, Taransay and the Sound of Harris, murmurings of giants and memories of “Splash” MacKillop “the crofter who hosted a prince”. A prince who is now King.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdContinuing north, he recounts visiting North Harris, Lewis, Scarp and the Shiants, which he describes from the sea as “the dusky sky appeared to be swarming with locusts, thick clouds of them swirling through the air. They were not insects, they were puffins, tens of thousands flying back and forth between the sea and their island burrows”.

The puffin colony there is the second largest in Europe apparently, and I read that around fifteen years ago, Europe’s oldest puffin, at 34 years of age, was found there. If it’s seabirds you’re after there’s nowhere better. But of course man has left his mark there too, in the form of stone built structures and the tell tale agricultural ridges of lazy beds.

For personal and sentimental reasons I was drawn to the chapter on Uig and the Flannan isles. It’s hard to capture the true beauty of a place with words, but Marc’s description of the Mangersta cliffs almost gave me vertigo.

I will leave the history for you to read, as I don’t like to be reminded of the bloody feuds between the MacAulays and my own ancestors, the Morrisons – those were troubled times, thankfully nowadays we are much more civilised, but in those early days of the 17th century, you’d have been well advised to stay inside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIsles of Loch Ròg offers a fascinating insight into Great Bernera and Little Bernera and explains how, as a result of the Riots, the latter communities’ strong sense of justice secured the crofters a place in history when they refused to move their grazing ground from the neighbouring Lewis mainland to an even smaller part of their own island. This would eventually lead to the implementation of the Crofters’ Act.

The last stop on his journey takes us to the islands of Rona, 40 miles north of the Butt of Lewis and beyond to Sulasgeir of the gannets. Through sea swells that threatened to scar me, Marc’s thirst for knowledge of the islands is quenched by these adventures.

This is a landscape of Gaelic place names and heroes – a wonderfully colourful book, that sings with the joy of the happy traveller.